Why do we have to die?

Let me first suggest that there is absolutely no need for you to read this, it’s really just me working through something. Move on to another blog post.

If we are to understand aging and death, the primary question is why should there be aging and death in the first place? What evolutionary purpose, if any, might they serve? First let me say that I’m discouraged that I don’t have any formal education in evolutionary biology, I think it’s a fascinating field and I’m frustrated by my status as a dilettante. Yet I proceed in the spirit of an amateur.

Established evolutionary theory holds that genes that lead to the death of an organism would not be adaptive and so aging and death are not part of some program. The current hegemonic aging theory is animated by the spirit that aging is a product of evolutionary neglect, not intent.

This is the theory of “accumulated mutations,” which holds that the organism accrues wear and tear from the processes of life, primarily genetic mutations that compromise function and lead to aging and death. We know that this is true, that over time organisms show an increased burden of DNA damage. This can happen because of errors in replication, it can happen from retrotransposons, or from free radicals, from radiation, toxins and all manner of other things. DNA damage is posited to be one of the hallmarks of aging.

The cell can repair DNA mutations and it has enzymes to do so, but this process is costly and to some extent the cell needs to balance repair-energy with growth-energy. If an organism devoted all its energy to repair, it would not win the evolutionary battle against the organism who went all in on growth and reproduction. The growth-organism would die earlier but it would outgrow and outcompete the long-lived organism into extinction–it would probably physically eat it. This state of affairs is referred to as “antagonistic pleiotropy,” meaning that survival to reproduction is prioritized by evolution and the very genes that improve survival to reproductive age lead to aging and death with the passage of time. Or put differently, genes that code to preserve the organism do not improve evolutionary fitness.

This aforementioned theory suggests that death is a by product of evolutionary fitness and is not some program. And yet I’m so tempted to think there is a program. Take development.. we see that an organism develops according to a certain path. Consider the well-worn path from embryogenesis through childhood and puberty. Even our deterioration after the young adult phenotype is patterned–consider male pattern baldness. These changes appear to occur as a non-random program. There are few bald adolescents, after all. I believe that aging is an extension of the same program as development (consider the Pacific salmon who swims upstream and suddenly dies) and this program has evolved for a specific reason. A non-immortal population benefits because there are increased iterations of natural selection and therefore increased chance of developing evolutionary fitness to a particular habitat.

The only way I can make this point is with a story, so let us consider the example of a nonhuman organism, an early mammal, though we could just as well pick a reptile or insect something else that is subject to sexual reproduction. Also one presumption–that a given population lives in a particular geography with limited natural resources.

Consider first the non-aging organism. At a certain point, the mature male will be competing for mating partners with males of the next generation. Given the evolutionary imperative to pass on genes, there will be competition, and since our mature male is larger and more experienced than the next generation, it will kill them. Alternatively, it will simply scare them off and prohibit them from mating. But killing them is better as it will prevent them from getting larger one day and becoming a legitimate adversary. Which is to say, those populations that evolve to infanticide will be better off. So now you have an immortal infanticidal creature that continues to mate forever. And if there is an accident or some lethal event, perhaps the accumulation of damage, the younger offspring can finally take his place. But you have a real limit on the amount of natural selection because the population genetics are all deriving from the same male, who is presumably the one mating with all the females.

On the other hand, in an aging organism, the old male always gets weaker with time and is superseded by the young males, who fight it out for the right to mate with the females. Because there is death, this arrangement maximizes iterations of natural selection which selects for better evolutionary fitness. Invariably this population will evolve more rapidly and will likely be better suited to survive in a difficult environment.

So aging and death can be considered an evolutionary advantage. Why couldn’t it be this simple?

Well, the question is what about the cheaters? What I mean is, what about the mutation that codes for long life? The thinking is that if there were some programmatic death, eventually some organism would develop the mutation to the program such that it lives much longer and thereby gains evolutionary fitness. But what I’m saying is that this would need to be balanced against the evolutionary fitness accrued by shorter lifespans. What I mean is whatever evolutionary benefit of more offspring accrued from longer life would be balanced by better evolutionary fitness from more cycles of natural selection due to shorter life.

This is the end of my brief career as an evolutionary biologist.

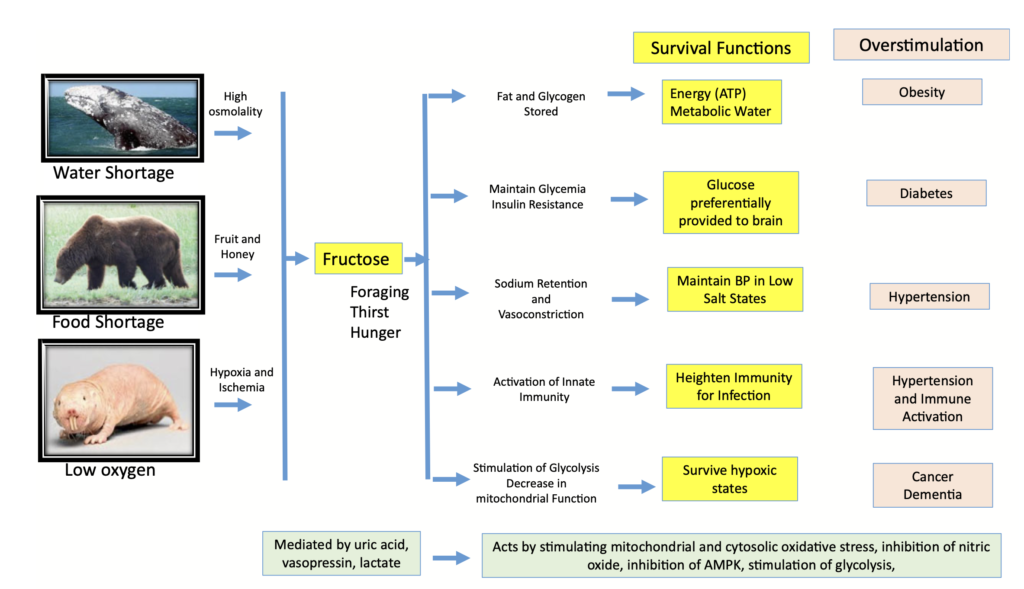

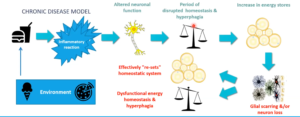

The two popular theories that purport to explain the obesity pandemic are the carbohydrate insulin model and the standard model of energy balance. In Why Nature Wants Us to be Fat, nephrologist Richard Johnson bravely proposes another theory: the survival switch.

The two popular theories that purport to explain the obesity pandemic are the carbohydrate insulin model and the standard model of energy balance. In Why Nature Wants Us to be Fat, nephrologist Richard Johnson bravely proposes another theory: the survival switch.

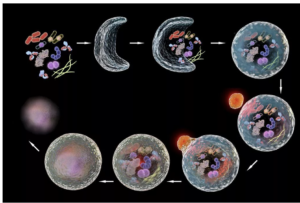

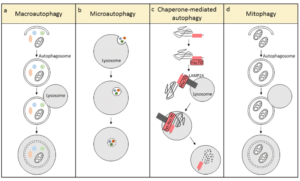

Autophagy (literally “self-eating”) is the body’s way of cleansing cells by recycling old or damaged components and is a process that appears to have a strong relationship to preventing disease and aging. More technically, it is a highly regulated lysosome-dependent catabolic program used by the body to clear dysfunctional proteins, organelles and other structures that are typically first marked for the process by a protein called “ubiquitin.” Primarily intra-cellular but also extra-cellular components are engulfed in autophagocytic vacuoles and degraded to constituent molecules, such as sugars, fatty acids and amino acids, which can be then be used as nutrition to produce ATP and/or provide building blocks for the synthesis of essential proteins. There are different types of autophagy but for the most part they all serve this same purpose. Mitophagy is a similar process that removes damaged or dysfunctional mitochondria. There is also nucleophagy of material in the cell nucleus.

Autophagy (literally “self-eating”) is the body’s way of cleansing cells by recycling old or damaged components and is a process that appears to have a strong relationship to preventing disease and aging. More technically, it is a highly regulated lysosome-dependent catabolic program used by the body to clear dysfunctional proteins, organelles and other structures that are typically first marked for the process by a protein called “ubiquitin.” Primarily intra-cellular but also extra-cellular components are engulfed in autophagocytic vacuoles and degraded to constituent molecules, such as sugars, fatty acids and amino acids, which can be then be used as nutrition to produce ATP and/or provide building blocks for the synthesis of essential proteins. There are different types of autophagy but for the most part they all serve this same purpose. Mitophagy is a similar process that removes damaged or dysfunctional mitochondria. There is also nucleophagy of material in the cell nucleus.

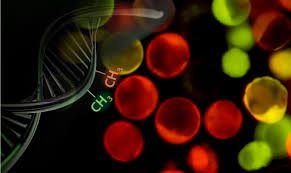

How do we measure aging? Certainly, there is the passage of time and how many birthdays someone has had, but we know that aging proceeds more quickly for some people than it does for others. The speed of aging depends on your genes but also various factors such as, for instance, whether you smoke, your diet and level of exercise, your stress levels, exposure to ionizing radiation, and many other variables. A 50 year old executive will likely be biologically younger than a 50 year old homeless alcoholic who has had a hard life, to take an example. Is there some other marker that indicates a biological age that is distinct from chronological age? This question is critically important if we are to assess the effectiveness of anti-aging interventions and has been a matter of much debate. Recently as our understanding of aging has evolved, scientists have focused on methylation patterns in the DNA as a likely proxy for aging.

How do we measure aging? Certainly, there is the passage of time and how many birthdays someone has had, but we know that aging proceeds more quickly for some people than it does for others. The speed of aging depends on your genes but also various factors such as, for instance, whether you smoke, your diet and level of exercise, your stress levels, exposure to ionizing radiation, and many other variables. A 50 year old executive will likely be biologically younger than a 50 year old homeless alcoholic who has had a hard life, to take an example. Is there some other marker that indicates a biological age that is distinct from chronological age? This question is critically important if we are to assess the effectiveness of anti-aging interventions and has been a matter of much debate. Recently as our understanding of aging has evolved, scientists have focused on methylation patterns in the DNA as a likely proxy for aging.

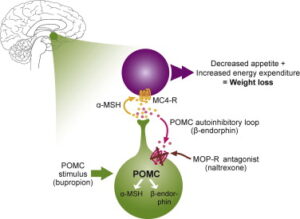

brain. Let us nerd out on the mechanism for a moment. Bupropion is an anti-depressant that has the unexpected effect of stimulating the cleavage of a large molecule called POMC. One of the cleavage products is a-MSH, which activates the melanocortin-4-receptor (MC4R), which reduces appetite and increases energy expenditure. Another cleavage product of POMC, beta-endorphin, feeds-back to inhibit cleavage of POMC. But that’s where naltrexone comes in, it blocks the inhibition of POMC cleavage, resulting in unopposed stimulation of MC4R. Beware though that naltrexone blocks the action of opiates more broadly, so if you take opiate pain medication, this drug is definitely not for you. However, Contrave does seem to have a role in attenuating addictive pathways in the brain, so it might be an appropriate choice for someone who wants to cut down on smoking and/or drinking.

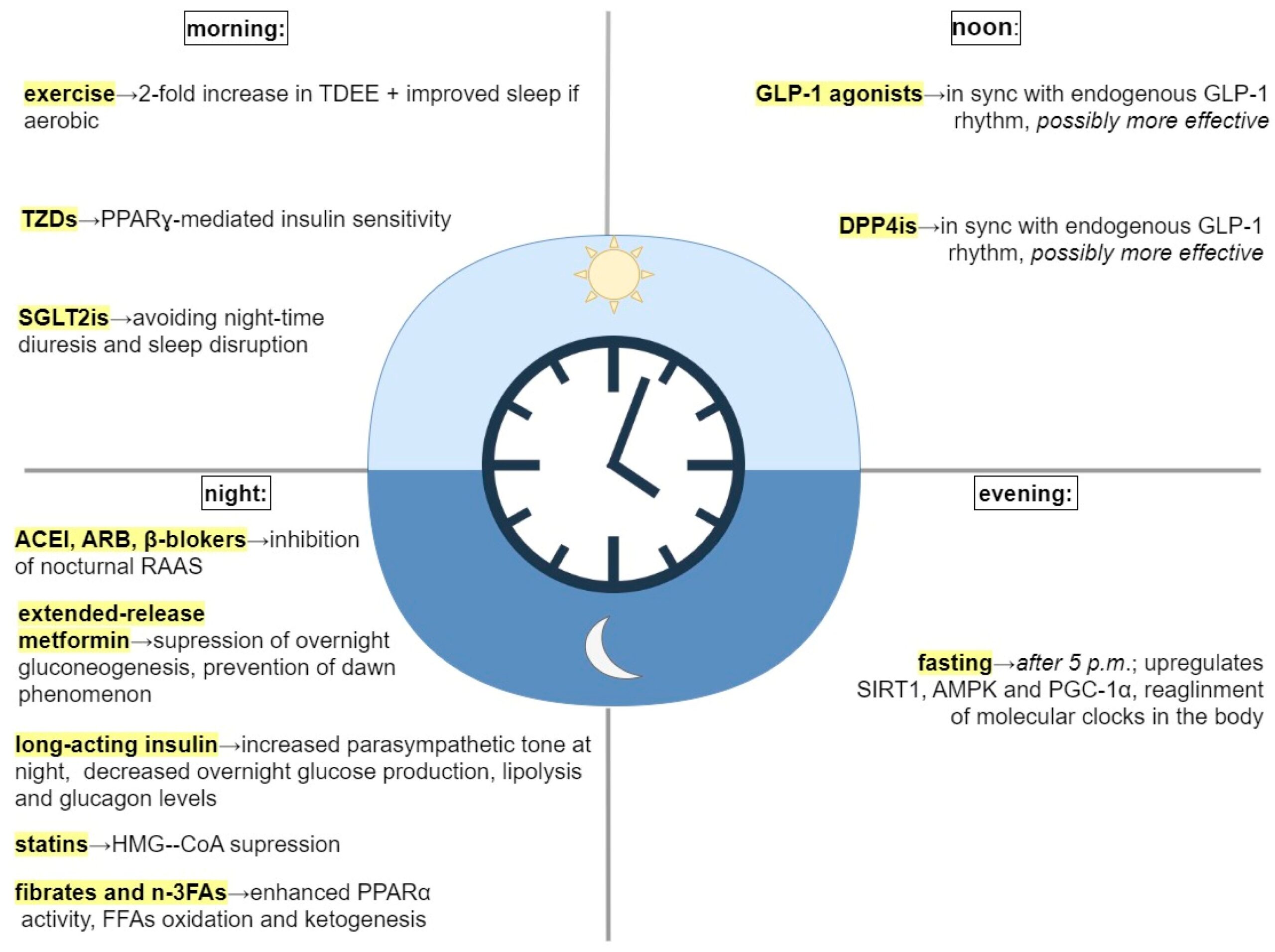

brain. Let us nerd out on the mechanism for a moment. Bupropion is an anti-depressant that has the unexpected effect of stimulating the cleavage of a large molecule called POMC. One of the cleavage products is a-MSH, which activates the melanocortin-4-receptor (MC4R), which reduces appetite and increases energy expenditure. Another cleavage product of POMC, beta-endorphin, feeds-back to inhibit cleavage of POMC. But that’s where naltrexone comes in, it blocks the inhibition of POMC cleavage, resulting in unopposed stimulation of MC4R. Beware though that naltrexone blocks the action of opiates more broadly, so if you take opiate pain medication, this drug is definitely not for you. However, Contrave does seem to have a role in attenuating addictive pathways in the brain, so it might be an appropriate choice for someone who wants to cut down on smoking and/or drinking. it’s a once-a-week drug that has been associated with loss of up to 20% of body weight. The drugs imitate the effect of a molecule called GLP-1, which has a range of effects including delaying emptying of the stomach, reducing appetite, and increasing the secretion of insulin. One would think that increased insulin is bad, but in one meta-analysis, GLP-1RA’s were associated with fewer strokes, fewer cardiovascular events, and lower all-cause mortality in a diabetic population.2 We’ll find out soon whether there is a decreased risk of major events for non-diabetics as well, but it makes this a very appealing medicine. In mice, a recent article suggests GLP1RA’s reduce brain aging.3 What are the negatives? First, the cost. They’re expensive, but if your insurance covers them, you’re lucky. If not, there are some other tricks to getting it at lower cost. Second, semaglutide, while once a week, is delivered as an injection–which is a bridge too far for some. Most importantly, when you take these medications, you lose muscle mass at the same time that you lose fat. But if you stop taking them, you gain fat. This effect is especially pronounced in people who are lean, so if you’re taking this medication to lose a few pounds in order to fit into a bathing suit, or a dress, you’re going to ultimately replace fat-free mass or muscle with fat. So mantra is that if you take this class of drugs you need to lift weights and develop your muscle mass, particularly lower extremity, buttocks, trunk and core muscles. Finally,

it’s a once-a-week drug that has been associated with loss of up to 20% of body weight. The drugs imitate the effect of a molecule called GLP-1, which has a range of effects including delaying emptying of the stomach, reducing appetite, and increasing the secretion of insulin. One would think that increased insulin is bad, but in one meta-analysis, GLP-1RA’s were associated with fewer strokes, fewer cardiovascular events, and lower all-cause mortality in a diabetic population.2 We’ll find out soon whether there is a decreased risk of major events for non-diabetics as well, but it makes this a very appealing medicine. In mice, a recent article suggests GLP1RA’s reduce brain aging.3 What are the negatives? First, the cost. They’re expensive, but if your insurance covers them, you’re lucky. If not, there are some other tricks to getting it at lower cost. Second, semaglutide, while once a week, is delivered as an injection–which is a bridge too far for some. Most importantly, when you take these medications, you lose muscle mass at the same time that you lose fat. But if you stop taking them, you gain fat. This effect is especially pronounced in people who are lean, so if you’re taking this medication to lose a few pounds in order to fit into a bathing suit, or a dress, you’re going to ultimately replace fat-free mass or muscle with fat. So mantra is that if you take this class of drugs you need to lift weights and develop your muscle mass, particularly lower extremity, buttocks, trunk and core muscles. Finally,