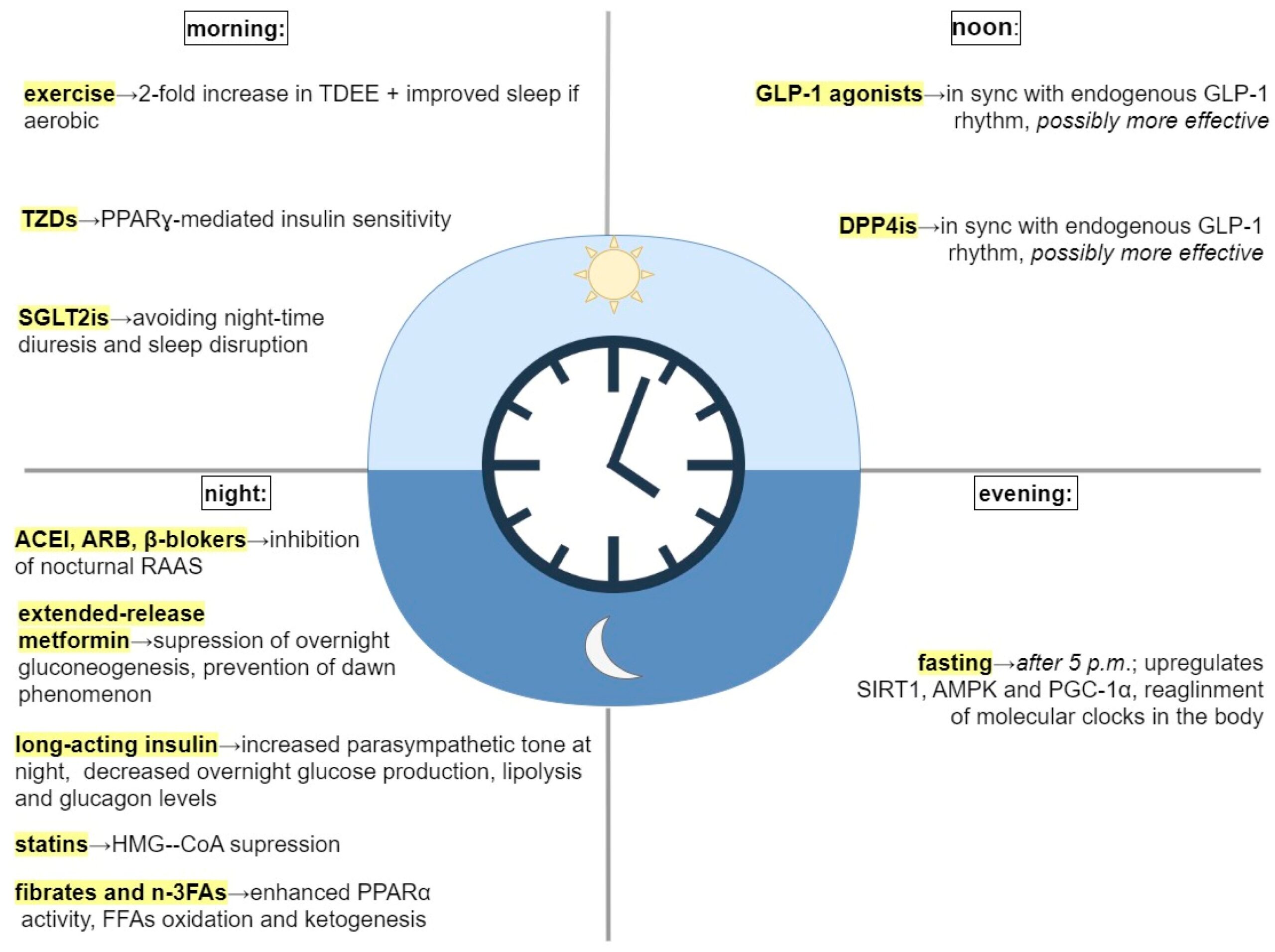

Circadian interventions

We have internal rhythms that align with the rotation of the planet. Most famously, there is the rhythmic secretion of melatonin at night and a spike of cortisol in the morning. These and myriad other oscillations are controlled by aptly named clock genes that are present in every cell of the body. Clock genes work together to maintain and synchronize the timing of various physiological and behavioral processes in the human body. Some of the key clock genes are CLOCK, BMAL1, PER, and CRY. The molecular clock in individual cells is synchronized by a master oscillator located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus. The SCN receives light signals from the retina, which helps to align the internal clock with the external light-dark cycle, ensuring that the circadian rhythm is properly entrained to the external environment. Circadian dysfunction that occurs when peripheral clocks are out of sync with the central clock, as during jet lag or shift work, can lead to metabolic dysfunction. The function of the clock genes and the mechanisms of circadian rhythmicity have been elucidated to fascinating detail–though their translation to clinical medicine has not happened. But according to this Montenegrin paper, circadian timing can be easily applied for interventions related to metabolic health.

Certainly the most obvious and best studied of the circadian recommendations is to align sleep with the day and night cycles. Following that, eating while the sun is out is a good rule of thumb, we know that eating outside a circadian window affects how we use our calories and increases the likelihood of metabolic dysfunction. Like many who practice obesity medicine, I suggest front loading calories earlier in the day.

Exercise in the morning–I’ve read different perspectives, but the paper makes a good case for timing exercise early. They point out that melatonin phase delays are associated with exercise in the evening or overnight.

Antihypertensives: ACE inhibitors and ARB’s should be taken in the evening–I didn’t know this. Blood pressure follows a diurnal rhythm—typically dipping at night. Administering certain antihypertensives (like ACE inhibitors or ARBs) in the evening can restore nocturnal dipping and reduce early morning cardiovascular events, which are more common due to cortisol surges and sympathetic activation

Statins: Should also be taken at night. Good to know. Put it on your nightstand. Cholesterol synthesis peaks at night, especially in individuals on low-fat diets. Short-acting statins like simvastatin are more effective when taken in the evening, whereas longer-acting ones (e.g., atorvastatin) are less time-sensitive.

Metformin: take it at night

Steroids: Endogenous cortisol peaks in the early morning. Administering exogenous corticosteroids like prednisone in the early morning mimics this rhythm and minimizes HPA axis suppression and insomnia.

Breakfast: Is it the most important meal of the day or should you skip breakfast to prolong your fast? It appears that calories eaten for breakfast are less fattening, account for more energy expenditure and may reinforce important clock genes. Which is to say, eat your breakfast.

GLP-1 RA’s in the afternoon to sync with endogenous GLP-1 secretion–probably less relevant since people take once weekly dosing.

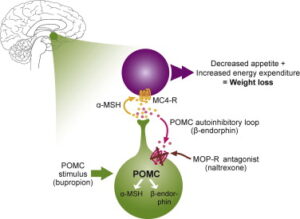

brain. Let us nerd out on the mechanism for a moment. Bupropion is an anti-depressant that has the unexpected effect of stimulating the cleavage of a large molecule called POMC. One of the cleavage products is a-MSH, which activates the melanocortin-4-receptor (MC4R), which reduces appetite and increases energy expenditure. Another cleavage product of POMC, beta-endorphin, feeds-back to inhibit cleavage of POMC. But that’s where naltrexone comes in, it blocks the inhibition of POMC cleavage, resulting in unopposed stimulation of MC4R. Beware though that naltrexone blocks the action of opiates more broadly, so if you take opiate pain medication, this drug is definitely not for you. However, Contrave does seem to have a role in attenuating addictive pathways in the brain, so it might be an appropriate choice for someone who wants to cut down on smoking and/or drinking.

brain. Let us nerd out on the mechanism for a moment. Bupropion is an anti-depressant that has the unexpected effect of stimulating the cleavage of a large molecule called POMC. One of the cleavage products is a-MSH, which activates the melanocortin-4-receptor (MC4R), which reduces appetite and increases energy expenditure. Another cleavage product of POMC, beta-endorphin, feeds-back to inhibit cleavage of POMC. But that’s where naltrexone comes in, it blocks the inhibition of POMC cleavage, resulting in unopposed stimulation of MC4R. Beware though that naltrexone blocks the action of opiates more broadly, so if you take opiate pain medication, this drug is definitely not for you. However, Contrave does seem to have a role in attenuating addictive pathways in the brain, so it might be an appropriate choice for someone who wants to cut down on smoking and/or drinking. it’s a once-a-week drug that has been associated with loss of up to 20% of body weight. The drugs imitate the effect of a molecule called GLP-1, which has a range of effects including delaying emptying of the stomach, reducing appetite, and increasing the secretion of insulin. One would think that increased insulin is bad, but in one meta-analysis, GLP-1RA’s were associated with fewer strokes, fewer cardiovascular events, and lower all-cause mortality in a diabetic population.2 We’ll find out soon whether there is a decreased risk of major events for non-diabetics as well, but it makes this a very appealing medicine. In mice, a recent article suggests GLP1RA’s reduce brain aging.3 What are the negatives? First, the cost. They’re expensive, but if your insurance covers them, you’re lucky. If not, there are some other tricks to getting it at lower cost. Second, semaglutide, while once a week, is delivered as an injection–which is a bridge too far for some. Most importantly, when you take these medications, you lose muscle mass at the same time that you lose fat. But if you stop taking them, you gain fat. This effect is especially pronounced in people who are lean, so if you’re taking this medication to lose a few pounds in order to fit into a bathing suit, or a dress, you’re going to ultimately replace fat-free mass or muscle with fat. So mantra is that if you take this class of drugs you need to lift weights and develop your muscle mass, particularly lower extremity, buttocks, trunk and core muscles. Finally,

it’s a once-a-week drug that has been associated with loss of up to 20% of body weight. The drugs imitate the effect of a molecule called GLP-1, which has a range of effects including delaying emptying of the stomach, reducing appetite, and increasing the secretion of insulin. One would think that increased insulin is bad, but in one meta-analysis, GLP-1RA’s were associated with fewer strokes, fewer cardiovascular events, and lower all-cause mortality in a diabetic population.2 We’ll find out soon whether there is a decreased risk of major events for non-diabetics as well, but it makes this a very appealing medicine. In mice, a recent article suggests GLP1RA’s reduce brain aging.3 What are the negatives? First, the cost. They’re expensive, but if your insurance covers them, you’re lucky. If not, there are some other tricks to getting it at lower cost. Second, semaglutide, while once a week, is delivered as an injection–which is a bridge too far for some. Most importantly, when you take these medications, you lose muscle mass at the same time that you lose fat. But if you stop taking them, you gain fat. This effect is especially pronounced in people who are lean, so if you’re taking this medication to lose a few pounds in order to fit into a bathing suit, or a dress, you’re going to ultimately replace fat-free mass or muscle with fat. So mantra is that if you take this class of drugs you need to lift weights and develop your muscle mass, particularly lower extremity, buttocks, trunk and core muscles. Finally,